A former member of a Utah firing squad, who asked to remain anonymous, says the process isn't bloody.

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- Former member of Utah firing squad says executions aren't gruesome

- Law enforcement officer volunteered for job, calls it 'another day at the office'

- Last execution by firing squad in Utah was 14 years ago

- Ronnie Lee Gardner is set to die by firing squad on June 18

Not because he was familiar with the 1996 case, or felt the need to deliver justice for a raped and murdered little girl.

It wasn't even because his high school classmate was raped and killed just before graduation.

So why did he do it? Why choose to join four other men in executing a convicted murderer?

"How often does this come along?" he says, "... 100 percent justice."

It's been more than 14 years since guns were last fired in Utah's execution chamber. But later this month, they may sound again, reviving a debate about the death penalty and the methods used to carry it out.

The one-time executioner met a CNN reporter in a Salt Lake City restaurant Tuesday to talk about his former role as Utah prepares to put Ronnie Lee Gardner before a firing squad June 18.

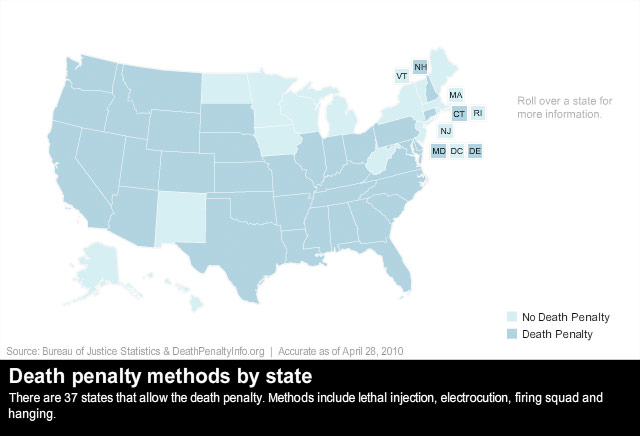

Death penalty methods by state

Death penalty methods by state The former firing squad member asked not to be named, as he remains a law enforcement officer in the state. The man he helped execute, John Albert Taylor, was sentenced to death for killing an 11-year-old girl in 1989. Charla Nicole King had been sexually assaulted. A telephone cord was wrapped around her neck -- three times, her mother told authorities. She knew because she counted as she unwound it, trying to revive her daughter

The officer agreed to recount his experience because he believes in the death penalty -- and thinks the firing squad method is plagued by misconceptions.

It is not like the scenes depicted in movies, with a condemned man tied to a stake and smoking a last cigarette before being riddled with bullets in a gruesome spectacle. Instead, he says over coffee, toast with grape jelly and an omelet, the process is instantaneous and carried out with the utmost professionalism.

"It was anti-climactic," he says. "Another day at the office."

It was anti-climactic, another day at the office."

--Former firing squad member

--Former firing squad member

Does he have any lingering effects from his role in the execution?

"I've shot squirrels I've felt worse about," he says. He volunteered to participate, he said, and would do so again, given the opportunity.

"There's just some people," he says, "we need to kick off the planet."

The officer remembers feeling a sense of responsibility that day, as he awaited the countdown to fire at Taylor, strapped into a chair 17 feet away with a target pinned to his chest.

He remembers telling himself, "Don't (expletive) this up."

The five men selected for the firing squad had been given a month to prepare. They practiced their shooting in the execution chamber.

On the day of the execution, four of the five were armed with live rounds. The fifth received an "ineffective" round that, unlike a blank, delivers the same recoil as a live round. No one knew who had the ineffective round.

Two alternate marksmen were on standby -- one to replace an officer who loses his nerve (none did) and a second to replace the alternate.

At the designated time, the five fired simultaneously. Only one shot was heard.

"They don't want to hear five shots," the officer said.

The former executioner has brought someone with him to the interview: Chris Zimmerman, once the police chief in Roy, Utah, who investigated the King slaying, interrogated Taylor, arrested him and witnessed his execution.

Zimmerman recalls seeing Taylor clench his fists as a reflex. His chest rose, and then sunk.

"The process was not gruesomely bloody, nor was it slow. "We were there, and it's not that way," the officer said.

He remembers getting home at 3 a.m. -- Utah executions are conducted just after midnight. Five hours later, he was kicking in a door to serve a search warrant.

There's just some people we need to kick off the planet.

--Former firing squad member

--Former firing squad member

"I do not want to downplay in any way what real cops do in real shootings."

Zimmerman points out that an officer who saw Taylor running from the murder scene with a gun and shot him would have been considered a hero. "Both ways, we killed him," he said.

He remembers King's mother telling investigators of finding her daughter's body and trying to resuscitate her before realizing it was fruitless, gently unwrapping the cord from the girl's neck.

"That woman has to live with that the rest of her life, and John Albert Taylor was put to death in seconds," Zimmerman said.

The officer points out that both Gardner and another death-row inmate in Utah, Troy Kell, were already in custody when they killed again. Gardner was charged with killing bartender Melvyn Otterstrom in October 1984; Kell was serving time for murder when he killed another inmate in a Utah prison.

No one executed for their crime, the officer points out, has ever killed again.

"It seems to be quite effective," he says. "Nobody's heard from Gary Gilmore," the first person executed after the Supreme Court lifted a ban on capital punishment in 1976. Gilmore died by firing squad at the Utah State Prison in 1977.

"You'll notice this didn't take two and a half hours," he says, referring to a recent execution in Ohio, where personnel had trouble finding a vein on an inmate to administer a lethal injection.

"The death penalty," the officer says, "is nothing more than sending a defective product back to the manufacturer. Let him fix it."

Asked about the arguments against the death penalty -- that one race receives it disproportionately, that the poor are more likely to wind up on death row -- the officer discounts them as procedural issues that should be fixed in the courts, not the execution chamber.

The death penalty is nothing more than sending a defective product back to the manufacturer.

--Former firing squad member

--Former firing squad member

And, he and Zimmerman say, polls show that most Americans support the death penalty. "The pulse of America is, 'Look, we're tired of this stuff,'" the officer says.

Utah was given permission to use the firing squad as a method of execution by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1879, according to the Death Penalty Information Center, a non-profit organization. Although one other state -- Oklahoma -- currently allows firing squad as a secondary method of execution, it can be used only if lethal injection and electrocution are ruled unconstitutional.

Firing squads are still in use in other countries; according to the Capital Punishment UK website, they are steadily declining. The site says there were 30 such executions worldwide in 2007 -- 15 in Afghanistan, one each in Belarus, Ethiopia, Indonesia and North Korea, three in Somalia and eight in Yemen. Some provinces in China are also thought to use the method.

Utah lawmakers outlawed the firing squad in 2004, but a handful of death-row inmates who had already chosen it as their execution method were grandfathered in after family members of murder victims begged the state Legislature not to open another door for appeals, lengthening what in many cases has become at least a 20-year wait for justice.

"The appeals process is a little out of control," the officer said. "Get it done in a couple of years and move on."

Asked about cases in which people are freed from prison after being proved innocent, the officer says he doubts there have been innocent people executed since 1976. It's hard to convict someone and put them on death row, he says, and it's harder to keep them there through numerous appeals. That process minimizes the risk of the innocent being executed, he says.

Taylor's death, the officer says, was a homicide in that it came at the hands of others. But it was not murder, he maintains, and the death penalty "needs to be used more often."

"I haven't lost three seconds of sleep over it," he says. "... it's true justice."